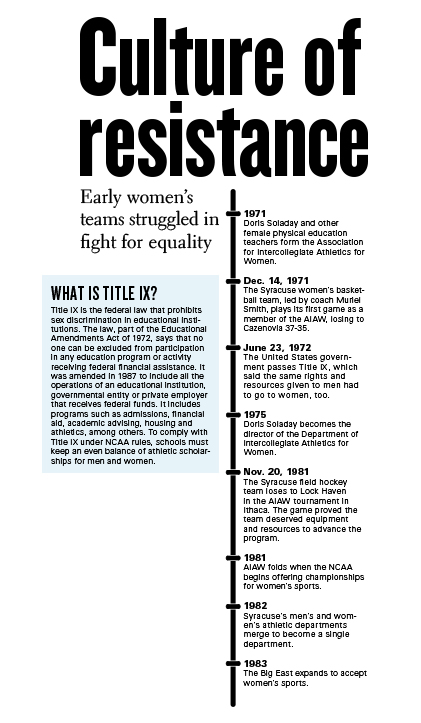

Culture of resistance: Early women’s teams at Syracuse struggled in fight for equality

Daily Orange file photos

Only now does the lunacy of the time come into clearer focus. Forty years ago, Muriel Smith didn’t consider driving the women’s basketball team to road games in a 12-passenger van to be abnormal. As the head coach, it was part of her job. She didn’t have an assistant coach on her staff. That would’ve been considered a luxury.

That was all Smith knew.

The legislation of Title IX in 1972 opened the door for women to play collegiate athletics. The progression was slow and the path to equality was rough. The first female athletes and coaches at Syracuse University fought a mindset from the top that they had to prove they deserved equality.

Asking for anything from uniforms to equipment was met with resistance from SU’s athletic administration.

“Of course when they passed Title IX, it was not a very happy atmosphere,” Smith said. “The kids were delighted, but I can’t say everybody was overjoyed about giving us anything.”

Before Title IX, opportunities for female athletes at Syracuse were limited. Kathrine Switzer transferred to SU from Lynchburg College in 1966 and wanted to start running competitively.

“When I got to Syracuse, I was really quite amazed that there were no women’s teams,” Switzer said. “It was really all intramurals, but the men had really high-powered teams.”

Switzer went to the men’s track coach at the time, Bob Grieve, and asked to train with the team. Grieve approved. But as soon as Switzer left the room, she was later told, Grieve turned to his two assistants and said, “Well, I think I got rid of her.”

Switzer showed up for practice the next day and ran with the men’s team. In 1967, she became the first woman to run the Boston Marathon.

At SU, the idea of a woman doing anything competitively seemed ludicrous.

Smith started working at Syracuse in 1968 as a graduate assistant while earning a master’s degree in physical education. She was also in charge of the women’s club basketball team, a group of eight or nine students who met once a week.

Over the course of four years, the group became anxious for more competition. They started meeting three to four times a week. The players bought T-shirts and added numbers with tape.

In 1971, Doris Soladay, who was an adviser to SU’s Women’s Athletic Association, joined a group of female physical education teachers who got together to form the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women. It was essentially the women’s version of the NCAA.

The AIAW organized games, and Smith and the Orangewomen began playing other local schools, including Oswego, Cazenovia and Buffalo.

The passing of Title IX on June 23, 1972, had little effect at first. Five women’s teams were established, including basketball, volleyball, tennis, fencing and field hockey. But the financial support for those teams was limited. Soladay became the athletic director for women’s sports, and even three years later, she still had a budget of only $50,000.

Margaret DeFuria, a 1972 volleyball team member, said the players had to buy their own practice clothes.

“We all went down to ‘M street’ and bought the same gray tops and had numbers put on them,” DiFuria said. “We bought our own shorts and everything.”

Smith’s basketball players had to share uniforms with the volleyball team, and the players weren’t given sneakers until 1976. While Soladay supported women’s athletics at SU, Smith said she didn’t give anything easily.

“My relationship with her was good, it’s just that she believed women didn’t deserve anything until they earned it,” Smith said. “And you don’t rock the boat.”

Respect for women’s teams was lacking as much as resources were.

Eileen Donnellan DiBartolomeo came to Syracuse to play field hockey in 1978. At the time, the team practiced in front of the Women’s Building on an unkempt field. Trying to play field hockey on the overgrown grass was almost impossible. The team’s head coach, Kathleen Parker, fought the athletics department and finally earned the chance to practice on the grass fields by J.S. Coyne Stadium.

The football team used the adjacent field. When football practice was over, the players would routinely walk through the field that DiBartolomeo and her teammates were using, not around it.

“We were definitely not taken as seriously as I would’ve liked. It got better as it went along,” DiBartolomeo said. “When I first got there, we were playing club teams and I was like, ‘Oh my goodness.’ But by my senior year, Kathleen got the team put together.”

One of the players Parker recruited was Eileen Lewis Habelow, a goaltender from Delaware who came to SU in 1981. That season was Syracuse’s last at the Division-II level before it moved up to Division I. The team also played for the Division-II national championship that year, losing to Lock Haven 2-0.

That game was critical for the advancement of the program, Habelow said. It proved the team should be taken seriously and deserved the resources it needed to compete at a high level.

Even Jim Boeheim paid attention.

Habelow was a senior in 1985, and as a social work major, she was working with a group of children in Syracuse. Looking to bring the group to a men’s basketball game, Habelow went to Boeheim’s office expecting to “grovel” for tickets.

When Habelow arrived at Boeheim’s office, he knew who she was, her position and her record. Boeheim said he’d be glad to get her the tickets.

It was a sign of changing times. Women’s teams were finally getting respect.

“When we went to D-I, a lot of the Title IX entitlements kicked in,” Habelow said. “So when we went D-I was when we started getting some cool stuff.”

Still, not everything was equal.

Barbara Jacobs took over the women’s basketball team from Smith in 1978. She had a recruiting budget incomparable to competing schools, and when she brought a recruit in, she had to sell the program on its family-like qualities. Jacobs had to get creative so the recruit did not focus on the team sharing a locker room with the volleyball players.

Jacobs said the women’s basketball team practiced in Manley Field House at the same time as the track and field team. At one particular practice, the hammer thrower lost control of the hammer and it smashed the trainer’s cart just inches from where the trainer was sitting.

Jacobs went to the athletics department and said it was unacceptable. The team needed its own gym.

The administration refused and told her to “work around it.”

“For me it was a challenge,” Jacobs said. “I wanted to be able to provide for my players what they deserved and I just kept working at it.”

When the team joined the Big East in 1983, the athletics department never painted the Big East flags in Manley, then the home court of the women’s team, so she had to do it. And when the team finally got its own locker room, which wasn’t until about 1989, Jacobs said she had to paint her players’ names above their locker in orange and blue paint.

“It was difficult, but at the time, I didn’t know it was difficult,” Jacobs said. “At the time, I was just doing what everybody was doing and just working hard to try and aspire to what the men had and trying to get some of that stuff.”

For the early women’s teams at Syracuse, that was a constant struggle. The female athletes of the early days of Title IX dealt with the challenges while their coaches fought for proper treatment and respect. Both came slowly.

At Syracuse, Smith said, little was given to women’s teams without a fight.

“You had to press for it,” Smith said. “But you don’t win friends by pressing for that kind of stuff when they don’t want to give it you.”

Published on October 1, 2012 at 2:56 am

Contact Chris: cjiseman@syr.edu | @chris_iseman